Out of the Box: Moving Beyond The Box

November 3, 2022The virtual event “Out of the Box: A Conversation About the Future of School” featured an afternoon of panels with the most influential voices in education. In this closing session, Jeff Wetzler, Co-Leader of Transcend and Co-Author of Out of the Box, moderates a stimulating conversation with Linda Darling-Hammond, President and CEO of Learning Policy Institute, and Kirsten Baesler, North Dakota Superintendent of Public Instruction. In this discussion, they explore the most pressing learning issues today and the role of innovation in addressing them. From unfinished learning to teacher workforce challenges, the conversation delves into the need for personalized education, supporting teachers, and reimagining the outdated factory model of schooling. The conversation also emphasizes the importance of policies that align with the realities of the learning process and prioritize equity. Even while addressing the barriers to modernization in education, the speakers offer hope and inspiration, highlighting the transformative potential of innovative approaches and the power of meeting students’ needs at the right time with appropriate supports.

Jeff Wetzler:

Hello, I’m Jeff Wetzler, Co-Leader of Transcend and a Co-Author of the Out of the Box paper. I am so delighted and honored to be here today with Linda Darling-Hammond and Kirsten Baesler to engage in our final conversation.

I’ll just give a word of introduction to each, although I’m sure neither needs an introduction, and then we will get right into the conversation.

Linda Darling-Hammond is President and CEO of Learning Policy Institute, President of the California State Board of Education, Professor Emeritus at Stanford, where she founded the Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy and is a recipient of numerous distinguished awards, including most recently the prestigious Yidan Prize, which will help to fund the EDPrepLab, which she was instrumental in launching.

Kirsten Baesler is the North Dakota Superintendent of Public Instruction, a position she has held since her election in 2012 and in subsequent re-elections. In addition, she’s the President-Elect of the Council of Chief State School Officers, also known as CCSSO. She had a 24-year career in Bismarck’s public school system as a Vice Principal, library Media Specialist, classroom Teacher and Instructional Assistant and she also served on the Board of the Mandan School District for nine years, including seven years as President.

There’s much more that we could say about both of you, but we’re delighted that you’re here and thank you for making time.

I thought I would start with a relatively broad question, which is, what do you see as the most pressing learning issues today, whether in your home states or more broadly across the country given that you both wear hats both in your states and nationally as well? What do you see as the most pressing learning issues and how are you thinking about the role that innovation needs to play to address them? Feel free, either one of you, to jump in.

Linda Darling-Hammond:

Kirsten, why don’t you start?

Kirsten Baesler:

Sure. So first, thank you so much for the invitation, Jeff, and for having this opportunity to talk about this important discussion about where do we go from here Out of the Box. The paper did such a fabulous job of laying out the challenges and I know we’ll dig more deeply into those barriers that we have.

But coming out of the pandemic, I would say [there are] the same issues that were there before the pandemic. I think the pandemic exacerbated them and brought them to a broader awareness for, not just educators that knew that they were there, but [to] a nation as a whole, we are aware of the problems that are existing and how the model of education just isn’t meeting the needs of all students anymore and that’s what we need to really focus on.

I would say from my perspective, from my lens, those issues are the same. It’s the unfinished learning that happens every year and it just is compounded and built upon. We have to address how we can better serve our students and allow them the time and the space, and pace, that they need to really deeply grasp and understand a strong command of all the knowledge, but more importantly the knowledge and the skills that are necessary for them to be productive citizens. So I think that’s across all content areas. I know that there’s a lot of focus on the science of reading and the reading loss, and now it’s eighth grade math. But I think across all subject areas, just really being able to address and develop and support systems that allow our learners the ability to develop their own agency and be in a space and in a pace that they will be able to master learning instead of being pushed through a series of standards.

Linda Darling-Hammond:

Yeah, I will plus-one on that and just say that in addition to [that] fact that we need to really be able to adopt a mastery-learning approach, as Kirsten just described it. We also have a broad set of things that students need to know and be able to do that include the capacity to learn to learn, the capacity to collaborate and to communicate, and all of those things that go beyond what we currently ask students to demonstrate on multiple choice tests where they fill in a bubble, then that’s got some marginal utility, but we’ve got to be helping students both become deep in their learning and to be able to use that learning in really productive ways that also include civic engagement and the college and career-ready skills that we’re worried about. Of course, there’s an equity agenda that we have had going on that we need to continue to deepen because access to these opportunities has been so unequal.

I would just reinforce that and say that we’re in a position where, we’re, as state leaders, where the crude regulations over many, many years are, were built up to enforce the factory model that was designed to be a standardized approach to education 100 years ago. And we have to move beyond that factory model to both personalize education and to enable people to learn deeply and be able to deal with the world that we’re in, where knowledge is exploding and technologies are changing, and we need to prepare our young people to be deeply knowledgeable and flexible in applying that knowledge.

Jeff Wetzler:

Thank you both-

Kirsten Baesler:

I would add-

Jeff Wetzler:

Please, go ahead.

Kirsten Baesler:

One other thing that I think the pandemic has exacerbated again, is our teacher workforce. Obviously we were worried about the teacher supply, the teacher workforce shortage before the pandemic, and they are an exhausted workforce. I know our healthcare [workforce] has been exhausted the last three years, [and] our education system has been exhausted. And then the reason that I bring that up is, as we talk about student outcomes, I am a firm believer that student outcomes will never change until adult behaviors change and we must better support our teachers. What we’re asking our teachers to do is really hard work and they need the support, the training, the infrastructure to allow them to be innovative, to teach [students]. And most teacher preparation schools aren’t working, aren’t preparing teachers to teach in this model. They are designed to deliver a teacher to fit into that old industrial model of school.

We have an existing workforce of teachers that want to do this for their young people, but it’s hard to teach in an innovative way, to be able to allow each individual learner to go at the pace and provide a space for individualized, personalized learning. [It’s] much harder work than developing a lesson plan that you deliver in a 50-minute time period and hope that you’re going to hit 90%. It’s much harder work that we’re asking our teachers to do in this new way of learning and this new way of teaching, educating. We as systems need to ensure that we are providing those adults their own ability and their own opportunity to retrain themselves in teaching. We allow them to change their adult behaviors so then student outcomes can change, as well.

Linda Darling-Hammond:

And just to piggyback on that, which is so true, we’ve got to do this together. There are schools of education. I worked in one and redesigned one that work[s] on this kind of pedagogy, but then if you send people out to schools that are factory model schools, then they can’t sustain it. So you’ve got to change the schools and the preparation and the professional learning all at the same time.

But when teachers have the opportunity to teach in ways that allow them to be efficacious with kids, that is the greatest joy for a teacher. I know from my own teaching, and I know Kirsten, you had this experience too. Giving them settings, and there are these redesign schools across the country that are providing settings in which kids can succeed and teachers can succeed, that allows teachers to want to stay. And I think one of the problems that we’re seeing now is that both kids and teachers are voting with their feet and leaving the public school systems that we have that are rooted in the factory model that don’t allow you to be efficacious, don’t allow kids to be efficacious in their learning or teachers to be. The declining enrollment that we’re seeing, the retirements and resignations that we’re seeing are all [signs] that the system has to change.

Jeff Wetzler:

Amen. Yes. And I think you’re both making such an important point, which is that one of the very hardest things we can ask of educators is to meet young people where they’re at, customize and personalize for them, help them grow in ways that are even beyond reading and math, in citizenship, in leadership, in entrepreneurship, et cetera, but do that inside the constraints of the factory design of school.

Linda Darling-Hammond:

It’s impossible.

Jeff Wetzler:

It’s impossible. It’s impossible. Maybe a heroic teacher can do it for a short period of time, but to do that in any kind of systematic, reliable, sustaining way is very, very challenging.

Linda, a follow-up question for you at the policy level, the paper, as you know, argues that well-intended policies have had an adverse effect on innovation in the sector. I’m curious if you agree with that and how you think policymakers at the state and federal levels can create space for innovation.

Linda Darling-Hammond:

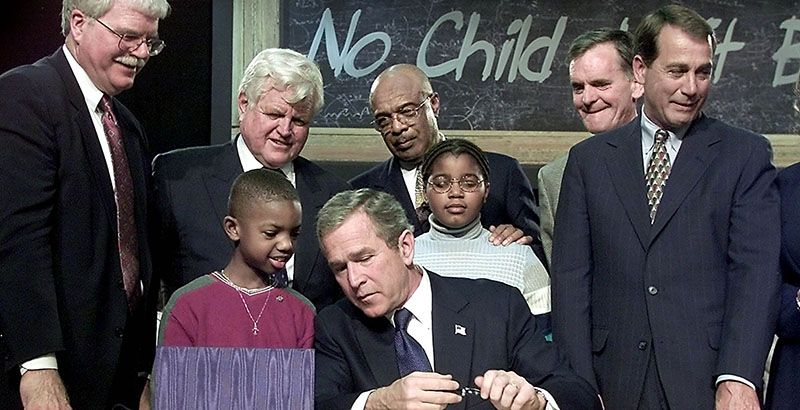

It’s a huge question. It’s something that keeps me up at night. I think about it all the time, but I mentioned the factory model that was brought into place in the early 1900s by Henry Ford and they modeled the school on the assembly line and the route to learning was a standardized route. You do the same thing over and over again, you stamp the kids with the lesson, they go to the next place on the assembly line, they get stamped with the next lesson, et cetera. That system was also not created for equity, although we often think about standardization as a pathway to equity. It was created with different conveyor belts for different kids. The eugenicists were involved in creating tests at that time, which they felt would sort people by race and class into the right conveyor belts. We’re trying to make this system and the regulations that uphold it meet a very different set of expectations and norms.

What are some of the things that stand in the way? Just as you were describing the notion that first of all, the notion that kids will move along at the same pace in the same way, and you can give them a standardized curriculum and give them a chapter, give him a test, give him a grade, move to the next chapter, test and grade. So pacing guides. Even the expectation in testing that is federally mandated [is] that we test and teach only the grade-level standards. It means that when kids have fallen behind, you’re not able to get right to where they are and give them what they need, and we know from the research that their acceleration will be much greater if every kid is motivated to do the next thing that they’re ready to learn, and it can be a success experience every day.

But to have to teach over the heads of some and under the heads of others in this routinized way, which has gotten reinforced, sometimes, because of an equity intention, but it ends up not having an equity effect. We know that variation is the norm. We know that people learn in different ways. We know that there are no two brains alike. There’s a lot of science now about that learning process, and we need to allow our policies to fit with the reality of the learning process so that educators can follow it.

Other things, seat time, instructional minutes, how you count, what counts as, learning. We all had to deal with that during the pandemic and the fact that kids can learn asynchronously online and synchronously online and in-person in internships and experiential learning, and sometimes in the high school, tuning into a college course and getting dual credit, all of those things that allow students to pursue their passions and to get the kind of education at the moment they need it so that they can accelerate their learning, require rethinking a lot of the rules that have evolved over many years in the system.

Federally, I’d like to see much more openness to innovations in assessment that allow us to assess kids as they’re going, where they are so that we can use it for teaching and learning, not for punishment, not for sanctions, but really for teaching and learning. I’d like to see accountability focused around the provision of opportunities to learn for students as well as for teachers. And I’d like to see us welcome and embrace the different models that are emerging for education that use technologies in interesting ways that allow kids and teachers to be bundled together and learning environments to be varied so that kids can get a much richer experience as well as a more personalized one.

Jeff Wetzler:

Thank you. And one follow-up to that. I think you point out a really important paradox, which is that some of the policies that may have originated with equity intentions may be the very policies that could be getting in the way of the kinds of innovations that you were just describing. As we think about policy going forward, whether state level policy or federal level policy, how do we avoid repeating that? How do we avoid now thinking this is great for innovation, but it might be at odds with equity in any way or said differently. What are some of the equity considerations we should be thinking about in innovation policy going forward?

Linda Darling-Hammond:

I think we have to think about equity as meeting students with what they need at the time they need it with no barriers and with supports. That’s what every parent wants for their child, what every child actually wants for themselves. When opportunity to learn what you need to know at the time you need to know it in a way that is meaningful and productive for you, when that becomes the definition of excellent and equitable education, we will see everyone learning at higher rates.

The other thing that we know from the science of learning is that we all learn to “mastery” by getting feedback on what we’re doing and revising that work and redoing it until we reach a higher standard. Which means you can’t just say, “give a chapter, give a test, give a grade, give a chapter, give a test, give it a grade,” and move people along this assembly line. Because the equity impact of allowing people to continue to revise their work until they learn actually narrows the achievement gap and allows everyone to learn more. So we’ve got to go with the science, we’ve got to help people understand it, we’ve got to show them the studies so that it’s clear that we can achieve more for everyone by being more rooted in the way the brain actually functions in the way teaching and learning actually need to occur.

Jeff Wetzler:

Thank you. Very helpful. Next question, in a moment in time where we are, a lot of people in education are, feeling tired. Educators have been working heroically, especially over the last few years on top of heroic work for decades and decades before that, it’s easy when you’re tired to lose hope. What are the things that you would say to educators, to school leaders, to system leaders that make you feel most hopeful about what’s possible going forward and that could offer hope as well to others?

Linda Darling-Hammond:

I mentioned redesign schools, that there are a lot of schools that much of this activity occurred in the 1990s, but we’ve got a resurgence of activity to redesign schools in a variety of ways. I know that Kirsten has a great example in North Dakota that she was just visiting. I hope she’ll talk about [that], we have them here in California, too. So we need to take hope from the folks who are forging ahead and rethinking the process and redesigning schools in ways that are working extraordinarily well. I do a lot of studies of redesign schools and I’ve designed some myself and really see the impact on kids. So I’m very hopeful based on that.

Teachers are, many of them, innately creative and driven to try to meet the needs of their students. If we give them environments in which they’re enabled to do that and learning opportunities that allow them to learn the strategies, I think we’ll see, as we are seeing in some parts of the country, real gains. And I think this is a moment where we’ve had the disruption and in these moments of human history where you’ve had great disruption, there is the possibility to redefine, and we have to seize that moment.

Jeff Wetzler:

Love it. Love it.

Kirsten Baesler:

And I would say, Linda mentioned the schools that are working in North Dakota and a couple things, and one of those schools that I was visiting about is Northern Cass. And Jeff, I know that Northern Cass works with Transcend, and I think that brings up two important points that I’d like to make about this work and what’s important. Partners are necessary, they’re absolutely necessary. School districts are charged with running and operating a school system on a day-to-day basis while they’re trying to change it. They can’t do that without partners. Partners are extremely important to North Dakota and extremely important to the work our North Dakota schools are doing. We try to beg, borrow, and steal. We have learned a lot from the school districts that Linda mentioned, Lindsay Unified in California. We learned so much at the beginning of our journey on this 10 years ago from Lindsay.

But Linda also mentioned that we have to do this together. And we were talking about that in the context of teacher preparation programs and school districts transforming. I would also say we have to do this together as state policy leaders, as leaders at the state level. We need to do that, we need to be alongside our teacher prep programs and our local school districts. I would say that the changes that we’ve been able to make in North Dakota policy and expectations have [come as] a result of those school districts coming to me as a State Superintendent to those Superintendents like Dr. Steiner and Northern Cass saying, “This is what’s standing in my way. We’ve discovered we want to do this and this is what’s standing in our way. Can you help us clear those barriers?”

I think as policymakers, it is critical. None of the progress that we’ve been able to make in North Dakota could have come without that school district saying to me, I could have a lot of great ideas on the tower at the Capitol and go to our legislators, which acts as my state board. We have a different system of State Board in North Dakota that… So it’s really the legislators that are my State Board that create the policy and provide the appropriation in a typical system.

When Corey came to me and said, “We need a different graduation pathway. This credit hour, the seat time, it’s not working. Can you help us develop a learning continuum that would be a pathway to graduation?” And without him asking us to do that, we would’ve maybe gotten in a different direction. It started seven years ago when we created the ability for the State Superintendent to waive certain aspects of our North Dakota Century code, and it was a matter of trust. The legislature gave my agency the authority to waive these. At first, it started out, [it] was interesting that I had the authority to waive any law in Century Code. And then somebody pointed out, well, she probably shouldn’t be able to change the speed limit, so let’s just limit it to the chapter in Century Code that is specifically K-12 education. I thought, “Okay, that’s a good compromise.”

But it allowed me to work with school leaders like Dr. Steiner and other leaders that said, “You come up with a great idea and make your case, why this is going to be better for kids and I will provide a waiver.” And so Dr. Steiner has been operating under a waiver for a number of years, for the last seven years that excuses him from many of the bureaucratic expectations that were put in place for the standardized industrial model.

We followed that up with Senate Bill 2196 which was the learning continuum, and we did something additionally, which is a separate bill that just said that we recognize that students learn anywhere and everywhere. It’s not just during their time, nine, ten months out of the school year in those seven and a half hours in that brick-and-mortar building. So we passed and allowed a Learn Everywhere bill that allows us a great leader like Superintendent Steiner and his amazing counterparts across the state to recognize that learning is taking place through 4-H or FCCLA and allow those students to demonstrate mastery of content while they’re working with their peers and others and giving them credit, if you will, towards their graduation pathway of the learning continuum.

I think there are specific things that each legislature can do [and] that state policy leaders can do. I would just caution all of those lawmakers and those decision makers to not try to do that from their own lens and their own perspective, but partner with those school leaders that know what they need and then design something that meets their needs.

Linda Darling-Hammond:

And then I would just add to that, I love that set of examples, that we do these things on waivers, we also can give waivers from the California State Board to certain rules and regulations and so on. But where we see that that makes a difference in the education for kids, we need to think about how do we change the system so it doesn’t have to happen on a waiver, so that this is not something that only happens on the margins when there are very proactive leaders who are willing to go against the grain. How do we change the grain? Is the other question.

Kirsten Baesler:

And I think that’s exactly the right question to ask. When we began on this journey in North Dakota nine years ago, that was our intent. We wanted to make this the way that we do education in North Dakota, not just some students in some zip codes, but all students in our entire 701 area code. We wanted it to be the way education was for every student in every classroom, in every building in our state.

As we use the waivers, that is how we were hoping, and we still hope, that those leaders that are courageous and brave, instead of worried about being perfect, they’re helping us find the way. The waivers are being used and should be used and we need to continue to do this and get better at this in North Dakota, as well. But we need to use what is being leveraged through waivers and simply change our regulations for the entire state. Not have a school district go through the exercise or the work of applying for a waiver, but if it has revealed itself that this isn’t working in our school districts, then let’s just simply remove that barrier, change the policy, change the regulation, so it isn’t just on the fringes and aren’t, there aren’t just a few schools doing this, but it’s the way that we do school and the way that we operate in K-12 education in our state.

Linda Darling-Hammond:

Exactly.

Jeff Wetzler:

One last question. This is the final session of this gathering of multiple different sessions. And so I want to give you each last word. I know with us right now we have policymakers and state leaders and funders and district leaders and school leaders and others who really care about [inaudible]. What would be your parting words to folks who are with us right now, maybe who’ve read the paper and who are asking themselves, “What can I do to make the biggest difference possible to create the conditions in my district, in my state, in my country to enable the types of learning environments that allow every young person to fulfill their greatest potential?” What would you want to leave people with?

Linda Darling-Hammond:

I think of education systems as three points on a triangle where we’re focused on meaningful learning, where we’re supporting that with professional capacity and where we’re resourcing it with equitable resources and opportunities to learn. The whole system of curriculum and assessment has to be focused, and this is a federal and state agenda on much more meaningful learning that is authentic, that is relevant to the world that kids are going to enter into that enables them to learn to learn and demonstrate their learning, and to do that in ways that are supportive of teaching and learning as a process. That means changing the federal constraints as well as some state constraints on what we think about in curriculum and assessment.

Professional capacity gets built by investing in teaching and teacher education and leader education. In other countries, if you want to become a teacher, you go there, you go to a high quality institution. If you’re in Finland, it’s got a partner school with you, that’s an innovative place that you’re learning to teach for free with a stipend while you’re training. You don’t have to go into debt to become a good teacher. You get mentoring, you get professional learning. Same thing is true for leaders. And then the resources are equitably available, that districts and schools that serve the kids with the greatest needs should get more money to do that so that we’re funding based on pupil needs and providing those resources. That’s the basket of policy that I think we need to focus on. As Kirsten said, moving from the innovative ideas of school leaders who need waivers to a system where that becomes the way in which we operate schools for the 21st century.

Jeff Wetzler:

Thank you. And Kirsten, I want to ask you the same closing question, which is, what would you want to leave people with?

Kirsten Baesler:

I think it’s important [that] schools are driven by accountability. SEAs, State Education Agencies, are driven by accountability. So I think at times we focus on accountability and we spend a great deal of our time ensuring that we are meeting the expectations within our accountability plans, whether it be the federal accountability expectations or estate accountability expectations. But what we need to do is to not leave accountability over there on the shelf is something we have to do.

When schools are engaged in the continuous improvement process as they go through accreditation and they’re looking for ways to improve, continuously improve all of the things that they’re doing, marry that with the accountability system. School leaders, state leaders shouldn’t be looking at those as two separate and independent activities or exercises. Use that accreditation process, that particularly the portion of your accreditation process that expects and demands that you reflect and have after-action reflection on continuously improving. Use that in conjunction with your accountability system so that there are two forces driving in the same direction. The accountability that is having you keep your eye on the ball as you’re operating the school under existing conditions, but then having the accreditation, the continuous improvement process, blend into that as you’re building that new system while operating the current one.

Jeff Wetzler:

Wonderful. Linda Darling-Hammond, Kirsten Baesler, thank you so much for joining us for your very wise and inspiring observations and suggestions for those who are with us today.

It’s a pleasure to be with you. Look forward to continuing the conversation.

More on getting outside the box

-

Read More

Read More -

Only Out Of The Box Solutions Will Tackle Root Cause Of What Ails Schools

November 2, 2022 | Michael B. HornRead More -

New report, “Out of the Box,” offers promising path to increasing educational equity and opportunity

October 13, 2022 | New ClassroomsRead More -

Transcend’s Jenee Henry Wood & New Classrooms’ Joel Rose: “It’s the model, stupid”

January 21, 2022 | The 74Read More