From Planning to Action: Advancing Tailored Acceleration

October 5, 2021

A new school year is well underway for K-12 public schools, but the challenges we continue to face will have a long-lasting impact unless we do something drastically different to solve for unfinished learning. Districts have now enacted their plans for reopening and are beginning to use newly enacted federal funds to address students’ unfinished learning. Conventional strategies, based on a one-size-fits-all traditional school model, will not suffice to meet these unprecedented challenges.

Without significant intervention, the fallout from the pandemic threatens the economic prospects for an entire generation of students, according to a recent report from McKinsey & Company. The report predicts that this generation of less-educated students could reduce the size of the U.S. economy by $128 to $188 billion a year as this generation enters the workforce.

In the first article of this blog series, my colleague Matt Peterson introduces the idea of tailored acceleration, a strategy to help students efficiently recover and build on their mathematical knowledge. If you have not read his piece, please take a look to learn about the foundational principles of tailored acceleration, including:

- high expectations for all learners,

- a precise understanding of each student’s starting point,

- a personalized plan that incorporates destination, timeframe, and program, and

- regular assessments to measure progress.

These insights are based on more than a decade of thoughtful research and development focused on the creation and implementation of new learning models. As part of New Classrooms’ Policy and Advocacy agenda, we also presented a comprehensive overview of tailored acceleration in our 2020 report, Solving the Iceberg Problem: Addressing Learning Loss in Middle School Math through Tailored Acceleration which has resonated in the field. In fact, this piece was recently highlighted by the U.S. Department of Education in a new report on evidence-based strategies to address the impact of lost instructional time.

In Matt’s second blog installment, he shared the six necessary components for developing a tailored acceleration recovery plan for schools:

- an underlying skill map or framework,

- diagnostic tools,

- prioritization on a strategic mix of skills to get students back on track,

- regular assessments to measure progress,

- meaningful parent engagement, and

- incorporating key program design choices.

In this final article of the series, we’ll focus on the policymaking and operational levers that can help districts and schools launch tailored acceleration.

Putting Tailored Acceleration into Action

Policymakers and education leaders who seek to create a tailored approach will need to create the space and flexibility for schools to embrace innovative approaches that promote individualized student learning experiences.

Encourage Schools to Embrace Learning’s Long Game

One way for districts or policymakers to reduce barriers is to give schools the option to set learning attainment targets that extend beyond a single school year. Current standardized accountability systems too often require all schools to adhere to annual attainment benchmarks. In our paper The Iceberg Problem, we discuss how to incorporate multi-year growth metrics in school ratings systems. While any measure in a state accountability system must be calculated annually, that need not preclude multi-year measures. States may choose to compare changes in proficiency rates over multiple school years as part of their growth calculations within their accountability systems. Schools could be rewarded for the degree to which student proficiency levels changed between the start of sixth grade and the end of eighth grade, thereby encouraging schools to adopt a long-term view of performance to strategically catch students up and move them ahead.

Another idea we propose in the Iceberg Problem is for states to weigh key transition points more heavily. Some states, such as Arizona, currently place extra weight on critical benchmarks, such as third-grade reading. A state could, for example, weigh the performance of fifth- and/or eighth-grade students on their respective summative assessments more heavily than other middle grade levels. This approach would emphasize the importance of high school math readiness and also allow schools to strategically take a longer-term view and get students back on track.

Embrace Adaptive Assessments

Current statewide assessment systems that focus exclusively on measuring skills and knowledge within a single grade-level are missing a major opportunity to embrace tailored acceleration. Innovative assessment systems could be created to be both adaptive and span multiple grades, while also being able to measure interim student learning throughout the year. It’s an approach that could shift the conversation from seat time, to a focus on mastery, at the local and state level. This process would also create a series of “feedback loops” of longitudinal comprehensive growth data, which give teachers a much more accurate window into what their students are learning and need to learn next.

Piloting State Adaptive Assessments

There are a lot of ways in which states can carve out the space for districts and schools to use and incorporate adaptive assessments into their school model.

An especially promising example to look at is Georgia’s pilot adaptive assessment program. In 2019, the federal government approved Georgia’s plan for a new adaptive assessment system, called the Georgia Measures of Academic Promise (GMAP), which will be administered three times during the school year. Read Georgia Department of Education’s application to the Innovative Assessment Demonstration Authority to learn more about the pilot.

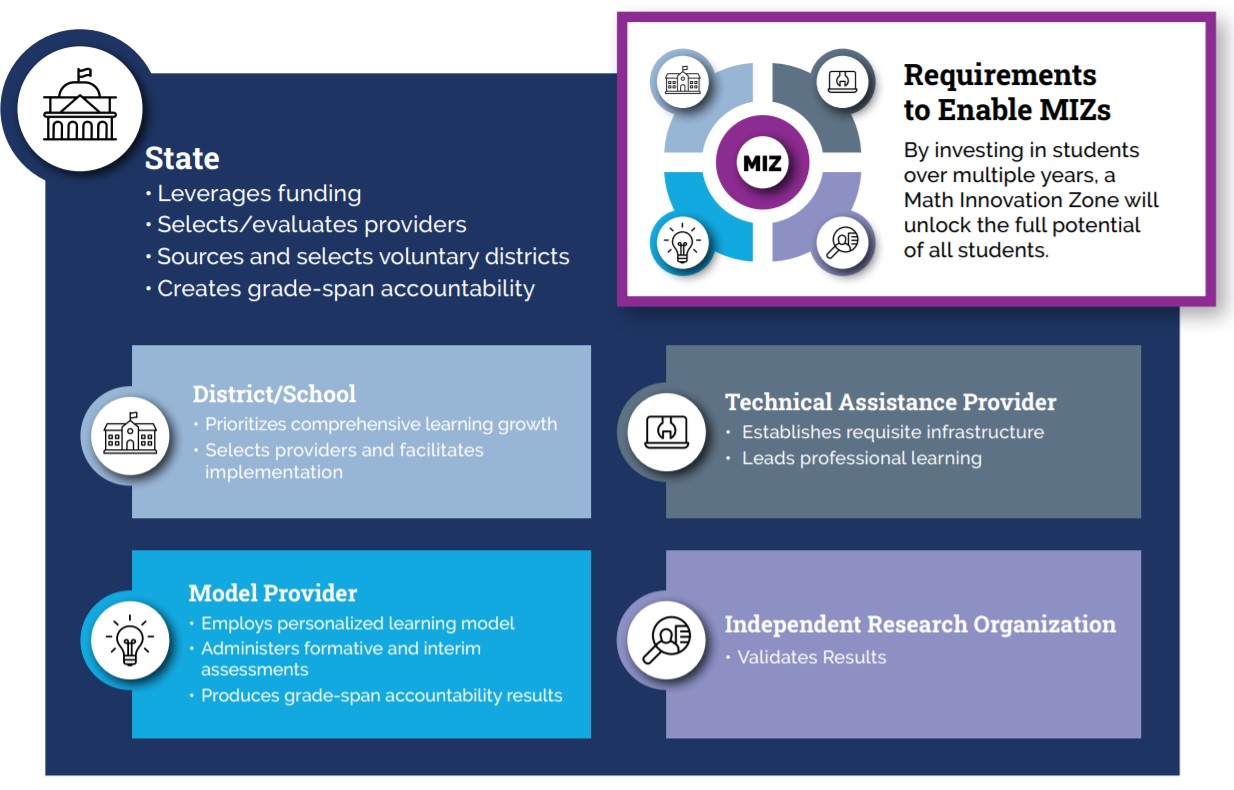

Launch Math Innovation Zones

Another promising state-led model for creating the space for innovation is the formation of Math Innovation Zones (MIZ) by the Texas Education Agency. In this program, participating districts, model providers, and technical assistance providers form partnerships which are guided by a state-developed framework. Together, they design a student-centered learning model that measures comprehensive learning growth through innovative formative assessments. States provide additional support and flexibility by removing policy barriers and designing student-centered accountability protocols.

Promote Viable Pathways in State Curriculum Adoptions

Another way to enable schools to embrace innovative learning strategies like tailored acceleration is to look at a state or district’s regulatory environment. Do textbook procurement processes promote curricular innovation that can enable tailored acceleration? Or do they reinforce the status quo and codify grade-level approaches?

Many states have policies that mandate textbooks be provided for all students, provisions that add extra hurdles and headaches for forward-looking district leaders who embrace innovative learning models.

Calling All District Innovators

To meaningfully address unfinished learning, the education system is going to need to embrace a wide range of innovative learning models and solutions such as tailored acceleration. For that to happen, district and state leaders will need to do everything they can to reduce barriers.

At the district level, superintendents and academic leaders often have greater flexibility than states. They have ambitious agendas for change and are often the biggest supporters of innovation, yet for a variety of reasons, they may feel unable to drive meaningful change. Especially now, given all of the enormous challenges districts and schools face in another year of uncertainty around safety protocols.

With the newly created American Rescue Plan (ARP) dollars, there are emerging opportunities in the not too distant future for district leaders to raise their hands to serve as laboratories for accountability and assessment innovation. Innovation zones in ARP state plans in places like North Dakota and Montana are two good examples of how states and districts can work together to better support more students.